Definition and extent of statelessness

A stateless individual is someone who is not “recognised” as a national by any country. Just to make it short, these people are not entitled not only to have a passport, ma even to ask for it! The number of stateless people globally is – at this time – still unknown. UNHCR data received from circa 96 countries indicates that, at the end of 2021, there were an estimated 4.3 million stateless people or persons of undetermined nationality. Based on these figures, the largest known populations of those who are stateless or of undetermined nationality can be found in Côte d’Ivoire (931,166), Bangladesh (918,841), Myanmar (600,000), Thailand (561,527) and Latvia (195,190)2.

International legal framework for protection from statelessness

There is an international legal framework to protect stateless persons and to prevent and reduce statelessness. The 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons (1954 Convention)3 sets out the international legal definition of a stateless person as someone “who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law” and extends to these persons specific rights such as the right to education, employment and housing as well as the right to identity, travel documents and administrative assistance. In this definition, nothing has been mentioned about access to health care service or the right to have a minimum standard health care protection.

The 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness (1961 Convention4) requires that States establish safeguards in legislation to prevent statelessness at birth or later in life, for example due to loss or renunciation of nationality or State succession.

The right to a nationality is also set out in several international human rights instruments and statement, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and the Migrant Workers Convention. Furthermore, customary international law reinforces the statelessness conventions through key norms such as the prohibition on racial discrimination, which applies to both the acquisition and loss of nationality and the treatment of stateless persons.

However, although almost all European states have signed up to international law standards on the protection of stateless people, most internal legislation based on National’s Magna Charta of different country, have to face the non-existence of effective national frameworks to put these commitments into practice. This has left many people facing discrimination and rights violations daily.

The solution to this problem is a strong national-based “political will”. States need to set up statelessness determination procedures as a regularisation route for stateless people who would otherwise be stuck in indefinite limbo. The limbo in which the risk to be put at-the-border on any health care protection policy is realistically concrete.

Encouragingly some countries have recently taken positive steps towards this goal. The Statelessness Index web page5 provides in-depth information and analysis on how countries within Europe are performing against their international commitments in this area (and others). The Index compares what countries are doing to identify and protect stateless people, including whether they have a dedicated procedure in place and how it stands up to scrutiny against international norms and good practice in areas such as procedural safeguards, evidentiary assessment, appeal rights, protection status, and acquisition of nationality. The Index highlights some good practice, but it also demonstrates that there is much still to be done. By the way, even in this circumstance, the minimum standard for Health care protection is vaguely mentioned.

“First and foremost, it has become clear stateless people are among those most adversely affected by the pandemic…” says Mr. Chris Nash, Director of the ENS*. “They are also often the first to react on the ground and support their communities. It is critical that stateless people and affected communities are heard and better resourced. Working together with stateless people, we seek to address the protection gaps exposed by the pandemic” 6. It is interesting to notice that in the ENS’s strategic plan 2019–23, SOLVING STATELESSNESS IN EUROPE – among different priority issues the ENS Advisory has identified four broad priority – the “health” themes is sufficiently “mentioned”.

Nevertheless, later the onset of COVID-19, the NGO’s representing the stateless community have stressed local authorities across Europe to ensure that healthcare systems meet the needs of the entire population, including the marginalised and disadvantaged and – over all – those who are not “present” in the territory based on paper-documentation. In most countries, legal status and formal documentation in fact are prerequisites for accessing quality and minimum standard healthcare. They are also prerequisites for gaining access to important social determinants of health, including employment, social protection, and adequate housing. Over 500,000 stateless persons in Europe, many belonging to minorities, do not enjoy the fundamental human right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law7. In a recent Report, provide by European Network on Stateless (ENS) in the 2021, Miss Dunja Mijatović asCouncil of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights as quoted as “COVID- 19 has demonstrated that the right to health cannot be protected at an individual level. It requires effective systems that provide for inclusive prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation for all, leaving no one behind and ensuring that structural inequalities are not magnified over time but disrupted and addressed8”.

Delving into some aspects of the ENS report Situation assessment of statelessness, health, and COVID-19 in Europe9, might also be useful to get a more global view on the state of the art of “needs.” The sociological survey was based on strict data collection mechanisms. Moreover, in the end it produced a set of recommendation that it might be useful to know a little more in depth.

In a broader context in terms of “rights,” the ESN Report clearly identifies some needs related to the “right to health” and suggests some “political” initiatives for states in the form of Recommendations.

Let us have look at the most relevant ones:

- States must guarantee the right to health of all on their territory, including stateless persons during and after COVID-19;

- States should consider regularising all stateless people during public health emergencies in order to guarantee the right to health. In the longer-term and where they have not yet done so, States should introduce mechanisms to identify and resolve cases of statelessness on their territory as well as statelessness determination procedures to guarantee stateless migrants the protection they are due under the 1954 Convention;

- States must uphold the protection of life and health for all stateless persons via appropriate disease mitigation and support measures in camps, shelters, settlements, social housing and immigration detention settings; and including those who are homeless. Stateless people and their communities no matter what setting (spanning community, accommodation centres, and immigration detention settings) must be provided with personal protective equipment (masks) and other basic necessities (hand-wash, soap, hot and clean water, towels);

- States must not detain stateless people under the pretext of disease prevention or containment. States are obliged to take steps to prevent the arbitrary detention of stateless people and ensure full access to rights and services whilst providing sufficient housing, health, and social care (including childcare) support on release from immigration detention.

It would be also interesting to have a look about the Statelessness Community in Europe. In December the 14th, 2015 the Conclusions of the Council and the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States on Statelessness was adopted. As consequences of the Conclusion, within the debate in the Justice and Home Affairs Council10 arrive the Conclusions to give the mandated to the European Migration Network11 (EMN) to establish a platform for exchange of information and goods practices. The Steering Board of EMN established the EMN Platform on Statelessness on 20 May 2016. The aim of the EMN Platform on Statelessness is based on the intention to raise awareness in regards with statelessness and to bring all the relevant stakeholders in the field together: representatives of Member States, European Commission, European Parliament, European agencies, international organisations, and NGOs. The first practical objective of this platform was to determine the state of play of statelessness in the European Union. In addition, The platform collects and analyses information on statelessness via the EMN ad-hoc query system. The most recent report EMN INFORM Statelessness in the EU, update version 4.0in November 2016 is available on line at this address/:/ https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/ 12. Is a very interesting Report as it delves into the legal situation of each European country in relation to Statelessness. For each individual member state of the Union, a whole range of issues is covered, in terms of the lack of rights and the weakness of each country’s protection system.

In conclusion, it is evident that the status of stateless often coincides with that of “undocumented” migrants. A condition of administrative irregularity that pushes to the bottom of civil society these figures deprived of any a guarantee of legality. In addition, it is increasingly difficult to address the issue of fundamental rights if this is strongly linked – inevitably – to the “bureaucratic” issue of a “simple” documents.

Any action to protect the vulnerabilities faced by those in a stateless condition in a country must necessarily start with a clear definition of the legal body of the stateless condition and that should be done at the level of Magna Charta for states.

Without a strong relevant philosophy and legal action and despite strong advocacy by civil society and international organisations including UNHCR during the pandemic, the data collected in the ENS, Situation assessment of statelessness, health, and COVID-19 in Europe shows that stateless people experience extraordinary vulnerabilities and rights violations in relation to health, but not only. It draws attention to their invisible nature in communities, policies, countries, and at the European level. It reveals a clear absence of specific empirical evidence and attention, by States, on the implications of statelessness for effectively addressing COVID-19. So, the main question is…what are the Consequences that Stateless People Encounter today worldwide? Without citizenship or a minimum process of “National recognition” based on the “territory”, stateless people have no legal protection at all and no right to vote and they often lack access to education, employment, and health care, registration of birth, marriage or death, and property rights. They have no access to life. Just survive to themselves, without past or future, and an uncertain present.

Palestine is perhaps the most famous of all modern cases of “statelessness”. What does it mean to be a national of a

state without formal recognition, especially over the course of many decades and generations? This issue is considered

in the bottom of the international political discussion, due to the long-time struggles in the Gaza’s area.

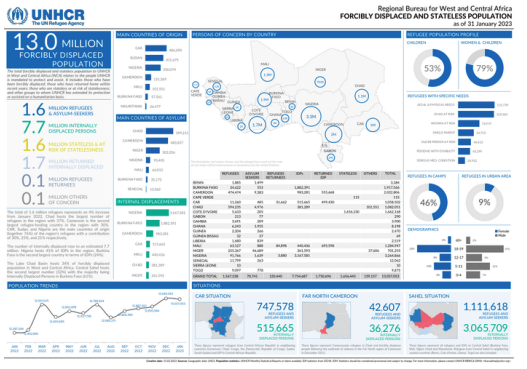

13.0 MILLION FORCIBLY DISPLACED POPULATION

The total forcibly displaced and stateless population to UNHCR in West and Central Africa (WCA) relates to the people

UNHCR is mandated to protect and assist. It includes those who have been forcibly displaced; those who have returned

home within recent years; those who are stateless or at risk of statelessness; and other groups to whom UNHCR has

extended its protection or assisted on a humanitarian basis.

[https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/unhcr-rbwca-forcibly-displaced-and-stateless-population-31-january-2023]

“Millions of people around the world are stateless. This is a matter of concern. The Convention on the

Reduction of Statelessness is an important tool for tackling the problem. Many States already have legislation

that is compliant with the provisions of the Convention and implementing it costs very little. Yet few States

are parties to this instrument.

We need to change that. I pledge the full support of my Office to governments wishing to become parties”.

António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations

https://www.refworld.org/docid/4cad866e2.html