INTRODUCTION 1

It is estimated that there are more than 200 million girls and women subjected to FGM in the thirty countries of Africa, Asia and the Middle East where such practices are most widespread, with adolescent girls representing the most affected population. At an international level, FGM has been the subject of multiple conventions aimed at eliminating this practice, considered a serious violation of the fundamental rights of women, with the consequent adoption at national level of measures aimed at this direction. The growing migratory flows from countries where such practices are still widespread make FGM a reality with which even health professionals must deal with in the light of current international and national legislation, with its important repercussions both in criminal law and civil law.

REGULATORY REFERENCES 2 3 4 5 6 7

Italy is a signatory country to a series of international conventions intended to eliminate FGM, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (1979), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990), the Declaration on violence against women (1993), which includes a particular reference to FGM, the Istanbul Convention of 2011, in which “violence against women is recognized as a form of violation of human rights and discrimination”.

According to the Art. 32 of the Constitution “The Republic protects health as a fundamental right of the individual and in the interest of the community. No one can be forced to a certain health treatment except by law. The law cannot in any case violate the limits imposed by respect for the human person”.

This article is recalled by Art. 5 of the Civil Code, which regulates the acts of disposing of one’s body, which are prohibited “when they cause a permanent decrease in physical integrity or when they are contrary to the law, public order or morality”.

The Law of 9 January 2006 n. 7 and art. 583-bis of the criminal code

Before the issuance of the c.d. Consolo Law, FGM could be classified among the intentional injuries pursuant to articles 582 and 583 of the Criminal Code; these, therefore, were punished as serious or very serious personal injury, in relation to the type of alteration produced on the woman and the consequences caused to her.

With the promulgation of the Law of 9 January 2006 n. 7 were dictated “the necessary measures to prevent and repress the practices of female genital mutilation as violations of the fundamental rights to the integrity of the person and to the health of women and girls” (art. 1). This provision is characterized by its dual character: on the one hand, as a repressive measure of violence against the human rights of every woman and, on the other, as an information-preventive tool.

The most relevant part of the legislative intervention consists of provisions of a penal nature. In fact, with article 583-bis, two new types of crime have been introduced: the crime of mutilation (C1) and the crime of injury (without mutilation) of female genital organs (C2), subject to verification of “actual triggering of a morbid process, producing an appreciable reduction in the functionality of the organs concerned”. It should be noted that, according to the law, the conduct causing the unlawful act can both be active and omissive, therefore there is a crime not only when the parent imposes genital mutilation on the daughter, but also when he/she does not prevent this practice from being carried out by the spouse, or by others.

The article clearly establishes that: “whoever, in the absence of therapeutic needs, practices mutilation of the female genital organs is punished with imprisonment from four to twelve years”. The mutilations of the female genital organs to which the Penal Code refers are: clitoridectomy, excision, infibulation, any other practice that reports effects of the same type. It is also specified that whoever, in the absence of therapeutic needs, causes lesions to the female genital organs other than those indicated above with the aim of impairing sexual functions, thereby causing a disease in the body or mind, is punished with imprisonment from three to seven years. The penalty will be more severe if FGM was practiced on a minor or for profit.

With the law n. 172/2012, implementing the Lanzarote Convention signed by Italy on 25 October 2007, the provision of the accessory penalty of forfeiture of the exercise of parental authority was introduced in article 583-bis of the criminal code. This forfeiture is regulated by articles 330 of the civil code (conduct that causes objective damage to children) and 333 of the civil code (conduct not such as to give rise to the ruling of forfeiture provided for by article 330, but in any case prejudicial to the child for which the judge can adopt the appropriate measures and order the removal of one or both parents from the family residence) . In 2018, the Court of Turin expressed itself with these provisions on a case of FGM.

It should be specified that the provisions of this law are valid even if FGM is performed abroad, both by an Italian citizen and by a foreign citizen residing in Italy. The Law also provides for an accessory penalty for those who practice a health profession (doctors, midwives, nurses), if they are convicted of any of these crimes, or the disqualification from the profession from three to ten years. In view of the prohibition, mutilative medical-surgical interventions are allowed, justified by the need to treat a patient’s pathology.

Within the scope of the law, reinfibulative cases are also illicit, in cases where the surgeon (where the suture has been removed for therapeutic reasons) is requested by family members or by the woman to carry out resuturing of the vagina.

Furthermore, the Code of Medical Ethics finally, in article 52, forbids explicitly to the doctor any form of collaboration, participation, or simple presence, in the implementation of acts of torture, or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatments and expressly precludes practicing any form of female sexual mutilation.

LEGAL OBLIGATIONS 2

With regards to the above, healthcare professionals should be aware of their responsibilities before the law, both with regard to the legitimacy of their conduct and with regard to their duty to inform the AG.

DISCLOSURE DUTY

Falling within the case referred to in C1 and 2 of Art. 583 bis of the criminal code in crimes that can be prosecuted ex officio, the Obligation to report to the Judicial Authority is in force for the Healthcare Professional.

This duty of disclosure must be fulfilled in accordance with the law in various ways, depending on the qualification of the Operator in the specific case.

The crimes that can be prosecuted ex officio are generally those against life, against individual safety (serious injuries, private violence, kidnapping), against public safety, sexual, abortion (outside of what provided for by Law 194/78), of tampering with a corpse, against individual freedom and against the family (mistreatment, abandonment of minors or the incapable).

Pursuant to Art. 331 c.p.p., Public Officials and Public Service Officers who, in the exercise or due to their duties or service, have news of a fact that could constitute a crime that can be prosecuted ex officio, have the obligation to report it. Therefore, the certainty of the crime is not necessary but the mere suspicion that it has occurred is sufficient.

Those who exercise a public function (activity carried out by a person not in his own interest but in the interest of the community) legislative, judicial or administrative, characterized by authoritative or certification powers hold the qualification of Public Officials (PU), pursuant to art. 357 criminal code. This is a manifestation of the will of the public administration. Among the figures who hold this qualification are the Medical Director of a public hospital, Hospital Doctors in the exercise of authoritative powers (in other cases they hold the position of Public Service Officers), the General Practitioner, the resident head of an Affiliated Laboratory, the Doctor who works in a private Nursing Home affiliated with the NHS. Pursuant to art. 358 of the Criminal Code, those who exercise a public activity, provided in any capacity and governed in the same form as a public function, hold the position of Public Representatives Service (IPS). However they do not hold the typical powers of public officials, i.e. authoritative or certifying powers.

Pursuant to articles 331 and 332 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the complaint must contain the exposition of the essential elements of the fact, the sources of evidence already known and the day of the acquisition of the news. The complaint must be presented and sent to the Public Prosecutor or to a Prosecutor’s Office in writing, without delay, even when the perpetrator is not known. In the event that several people are obliged to report the same fact, a single deed may be drawn up and signed by all the obliged parties.

According to the Art. 334 c.p.p. (Report) and the art. 365 criminal code (Omission of report), the Operator of a Health Profession (EPS) who has provided his assistance or operates in cases that may present the characteristics of a crime that can be prosecuted ex officio has the obligation to report, a possibility that must be concrete. The health professions in the Italian legal system are all those professions whose operators, by virtue of a qualifying title issued/recognized by the Italian Republic, work in the health field (pharmacist pursuant to Legislative Decree 258/1991; surgeon pursuant to Legislative Decree 368/1999; dentistry-tra ex l.409/1985; veterinarian ex l. 750/1984; psychologist ex l. 56/1989).

There are also nursing health professions ex l. 905/1980 and obstetricians ex l. 296/1985, as well as pediatric nurse ex d.l. 70/1997; to these are added the rehabilitation health professions, as well as technical-health professions (of the technical-diagnostic and technical-assistance area).

Pursuant to the aforementioned art. 334 c.p.p., the report must contain the indication of the person to whom assistance was provided, the place, time and circumstances of the intervention, as well as information regarding the fact, the means by which it was committed and the effects that it has caused or may cause. It must be sent in writing to the Judicial Authority within forty-eight hours or, if there is danger in the delay, immediately. As with the report, even if several people are obliged to make a report for the same fact, a single deed may be drawn up and signed by all the obliged parties. Like the provisions for the report, the omission or delay of the report is sanctioned but, unlike the report, there are exemptions from the report obligation (art. 365 of the criminal code): when the presentation would expose the assisted person to criminal proceedings (priority of the Right to Health); if the doctor has failed to submit a report due to having been forced to do so by the need to save himself or a close relative from a serious and inevitable harm to freedom or honor (Article 384 of the criminal code).

In summary, the substantial differences between the two cases described above concern the qualification of the obliged subject when he becomes aware of the fact (PU/IPS vs EPS), the ways in which he becomes aware of the fact (news vs pre-stare assistance /work), the timing with which the obligation must be fulfilled (without delay vs < 48 h/immediately), the certainty of the occurrence of an event that can be configured as a crime that can be prosecuted ex officio (suspect vs concrete possibility) and, finally , the presence of any exemptions (envisaged only for the report).

The main differences between the complaint and the report are summarized in table 1.

| REPORT | MEDICAL REPORT | |

| Qualification of the operator at the moment the subject is aware of the fact | PU/IPS | EPS |

| Method with which the subject has knowledge of the fact | NEWS | Assistance Provided |

| Time with which the obligation must be fulfilled without delay | NO DELAY | <48h / immediateley |

| Exemptions | NOT PROVIDED |

Table 1 Main differences between the complaint and the report

Since FGM, as mentioned, according to the provisions of Article 583-bis of the Criminal Code C1 and C2, types of crimes that can be prosecuted ex officio, the obligation to provide information is in force for the Healthcare Professional, according to the methods specified above. The ratio of the report lies not only in the prosecution of the crime already committed, but in a prevention perspective, both to protect current potential victims and future generations. This fulfilment, however binding, must be carried out by the Healthcare Professional as far as possible in alliance with the assisted, possibly with the support of Cultural Mediators and Social Services, in order to minimize the risk of her being removed from the network for family and sociocultural reasons.

THE PROBLEM OF CONSENT 2 8 9

Not insignificant are the problems relating to consent (i.e. the ability of the individual owner of the protected property to self-determination and freely choose) to this practice, taking into account the possibility, far from rare, that it is the victim himself who asks for be subjected to a culturally shared and socially imposed practice. One may consider it intrinsic to one’s cultural identity and, consequently, important for maintaining adherence to one’s own traditions.

In addition, a healthcare professional may be required to perform FGM on a minor or a disabled person.

Informed Consent is defined and regulated, for the first time in Italy, by law 219/17 containing “Regulations on informed consent and advance treatment provisions” – also known as the law on Biotestament. The law is structured in two parts: the first (articles 1, 2 and 3) deals with informed consent, the second (article 4) with living wills (the so-called DAT, advance treatment provisions) and planning shared care (art. 5).

Informed consent represents the very personal right of the patient to self-determination which takes the form of the faculty to choose freely and in full awareness between the various therapeutic treatment options, as well as that of refusing treatment and consciously deciding to interrupt the ongoing therapy.

The choice follows the presentation of a specific series of information, made understandable to him by the doctor or medical team.

Anyone who is directly involved in a medical act, if of age, conscious and capable, must give their consent to the health personnel so that they can act legitimately.

Given that it is a free and conscious manifestation of will, some subjects may not be in a position to meet these requirements. No distinction is made between minors, interdicted and incapacitated, we generally speak of incapable patients. The incapable patient “must receive information on the choices relating to his health in a manner consistent with his abilities to be put in a position to express his will”, as stated in the art. 3 paragraph 1 of law 219 of 22 December 2017. In such cases, the consent is expressed by the tutor or by the same disabled person.

Informed consent is used to make a certain health act lawful, in the absence of which the crime is committed again.

In the case of FGM we are faced with an act that has no therapeutic value (to which the assisted person may or may not give his/her consent), since, in particular as regards the provisions of C1, these are actions aimed at producing a disability of the psycho-physical integrity of the person and, as such, liable to prosecution by law.

Therefore, specifically, in addition to the Penal Law and the Deontological Code (art. 52), the provisions of art. 5 c.c. (“Acts of disposing of one’s body”, which are prohibited when they cause a permanent decrease in physical integrity, or when they are otherwise contrary to the law, public order or morality), except in cases expressly provided for by the Law (L. 458/67: living kidney transplantation; L. 164/82: rectification and attribution of sex; L. 107/90: blood transfusions; L. 30/93: sampling and grafts of corneas; L. 91/99: removal and transplantation of organs and tissues; Law 483/99: partial liver transplantation).

Can the woman therefore (or the guardian in the case of minors or disabled persons) express valid consent to these procedures? Are they specifically the holders of the existing right?

With regard to C1 of Article 583-bis of the Criminal Code, considering that these practices always result in a permanent decrease in psychophysical integrity (a right constitutionally guaranteed by Article 32), they cannot in fact express this consent.

Then, with regard to the crime of injury referred to in C2, there is no doubt that some types of FGM (e.g. practices which involve piercing, perforation, incision of the clitoris and labia) do not necessarily produce a permanent decrease in the psychophysical integrity which must be documented if necessary. Therefore, in this case it is possible to express consent to these practices pursuant to Law 219/17, and here, for example, the woman can legally request that a genital piercing be affixed to her.

As regards the discriminating factor referred to in art. 51 of the criminal code, the right referred to could consist in the right to religious freedom, or in that arising from custom, or provided for by a foreign law. However, it should be noted that no religious denomination compulsorily prescribes FGM and, even if this were the case, the exercise of freedom of religion cannot lead to the infringement of higher-ranking constitutional rights, such as personal dignity (Articles 2 and 3 Const.), physical integrity and psycho-sexual health (art. 32 Const.); therefore, in the case of FGM, not even the disclaimer pursuant to art. 51 criminal code.

Finally, please note that Law 219/17 in art. 1 paragraph 6 specifically states that the patient cannot demand health treatments contrary to the law, professional ethics or good clinical-assistance practices and that, in the face of such requests, the doctor has no professional obligations.

As far as defibulation is concerned, however, it does not integrate the crime set out in art. 583-bis of the criminal code since it is connected to a therapeutic need, aimed at repairing a serious violation of the physical integrity of the woman and of her right to health. Like other medical acts, it always requires the acquisition of a valid informed consent, also with the help of a cultural mediator where there is a need. In the case of minors, the persons exercising parental responsibility must be involved in the decision-making process, bearing in mind however that, in any case, the subject of protection is the right of the minor to see a serious violation of her physical integrity and her right to health. This must be in harmony with the provisions of art. 3 of the aforementioned Law 219/17 as well as in the case of the adult and incapable subject.

INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION 9 – 31

A person who is at risk of being subjected to female genital mutilation (FGM) can ask the Italian State for recognition of international protection, a set of fundamental rights recognized by Italy for refugees.

Refugees are people who have a well-founded fear of being persecuted in their country for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, belonging to a certain social group and who cannot receive protection from their country of origin. From this point of view, FGM is considered persecution that confers the right to the condition of refugee. This condition provides, in fact, for subjects to receive international protection and first of all to have guaranteed the right not to be repatriated and to stay in Italy.

Asylum applications for reasons of FGM can fall under Legislative Decree 251/2007 art. 7 and 8, which consider physical or psychological violence or acts specifically directed against a specific gender or against children as relevant for the purpose of granting refugee status. On the basis of the principles set out in the 1951 Geneva Convention, these acts of violence amount to a serious violation of fundamental human rights. Nonetheless, even having removed oneself or having removed one’s daughter from such practices may be considered for the purposes of requesting asylum applications, potentially implying a persecution of a political nature in countries where FGM represents a practice strongly rooted in the religious political order. This reason for persecution is specifically provided for by the aforementioned Legislative Decree. The same applies to those who have already undergone FGM, as they may have legitimated and well founded fear of future persecution and the same can be repeated and/or re-inflicted in different forms. The law includes, in fact, both hypotheses of past and future persecutions (articles 2, 3 and 4). The inclusion of FGM among the reasons for accepting asylum applications has also been reiterated in the context of European Union law and by the UNHCR. On this point, it should be noted that as early as the 1990s, the jurisprudence of various European countries, such as France, the United Kingdom, Austria, Germany, Belgium and Spain, and non-European countries, such as Canada, the United States and Australia , identified FGM as a precondition for the recognition of refugee status.

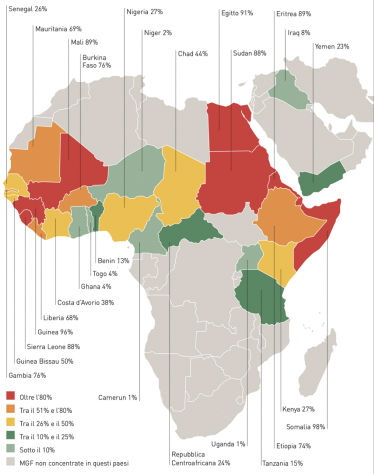

In 2016, Italy recorded an increase in migratory flows, especially from countries at risk of FGM, estimated at around 181,500 people, with a parallel increase in the number of asylum requests, for which it was the third EU country with 123,000 questions. Although the exact number of women who seek asylum for reasons related to FGM and who obtain it for this reason is not known, these data make it likely that in this population there is a high percentage of women who have suffered or are at risk of suffering FGM, considerations strengthened by the evidence of the high number of women asylum seekers from countries where the practice of FGM is still widespread: high numbers both in absolute terms, as in the case of Nigeria and Eritrea (which had an incidence of FGM equal to 27% and 89% respectively), and relative terms, as in the case of Somalia where the incidence of FGM was equal to 98% (Fig.1). It is estimated that in Italy there are between 60,000 and 81,000 women subjected to a form of FGM in childhood.

Figure 1: FGM by country among women aged 15-49 31

The burden of proof is on the applicant and it is sufficient to prove the credibility of the facts even circumstantially (C.C. sentences n. 18353/06, 10177/11 and 6880/11).

As regards the healthcare professional (mainly Specialists in Gynecology and Obstetrics and Forensic Medicine), they may be required to certify the existence of the mutilation, its typology and extent in order to correctly process the application.

COMPENSATION FOR DAMAGES 9 32 – 36

In civil law, the protection of victims of FGM raises the question of the possibility of compensation for the biological damage caused to them by such practices.

This cannot be separated from a medical-legal assessment concerning not only the assessment of the existence of a legally relevant causal link between the aforementioned practices and the residual injury at a psycho-somatic level but, above all, the transience or permanence of the outcomes themselves. Furthermore, it is advisable to consider the existence of disabling outcomes not only from a physical point of view, but also from a psychic point of view, as these practices are recognized to be very effective in terms of psycho-traumatic outcomes. The repercussions on the functioning of the victim are so considerable that they can configure a framework of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. An example is given of a sentence condemning compensation for damages in a case of FGM issued by the Court of Appeal of Turin on 26.02.2020 and subsequently confirmed in Cassation in 2021.

Having understood the damage as “the injury to the psychophysical integrity of the person, susceptible to medical-legal assessment, which is compensable regardless of its impact on the income-producing capacity of the injured party” (art. 5 paragraph 3, Law 57/01 ), the medical-legal assessment must be undertaken. It is done possibly in collegial action with a specialist of merit in cases that present the profiles of medical professional responsibility as provided for by law 24/17, and it will have to verify the existence of the impairment, its extent and any functional repercussions on the patient’s psycho-physical health.

CONCLUSIONS

FGM is recognized as a serious violation of the fundamental rights of women and girls and, for this reason, condemned by a series of international conventions which aim to eliminate such practices. In these conventions Italy is also a signatory. In the light of this, in the Italian legal system the practice of FGM, in violation of constitutionally guaranteed rights, entails a series of consequences both in the criminal sphere, in particular the cases referred to in 583-bis of the criminal code introduced by l. 07/06, and in the civil sphere relating to parental responsibility, international protection and, last but not least, compensation for the damage suffered.

As far as healthcare personnel are concerned, the law provides for an accessory penalty in the event of the practice of FGM, which are also expressly prohibited by the Code of Medical Deontology. Furthermore, since these are crimes that can be prosecuted ex officio, the duty of informing the Public Administration is in force for the doctor or the health professional, a duty defined differently according to the qualification held by the health professional.

Another critical element is the issue of consent. In the case of FGM we are faced with an act that has no therapeutic value (to which the assisted person may or may not give his consent). This is due to the fact that, in particular as regards the provisions of C1, it concerns actions aimed at producing an impairment of psycho-physical integrity of the person and, as such, liable to prosecution by law. Therefore, in addition to the Penal Law and the Code of Conduct, the provisions of art. 5 c.c. apply. Finally, please note that Law 219/17 in art. 1 paragraph 6 specifically states that the patient cannot demand health treatments contrary to the law, professional ethics or good clinical-assistance practices and that, in the face of such requests, the doctor has no professional obligations.

The case of deinfibulation is different, as it responds to a therapeutic need aimed at repairing a serious violation of women’s rights, thus not integrating the crime pursuant to art.583-bis but remaining in any case bound by the provisions of law 219/17 both for the capable adult and in the case of minors or incapable subjects.

Regarding the recognition of refugee status, the reasons contemplated by Legislative Decree 251/07 may include FGM as serious violations of fundamental rights directed against a gender or social group. This is also stated by subsequent European directives and guidelines of the UNHCR as well as by some judgments at the Italian level. Finally, with regard to the aspect of the biological damage resulting from FGM and its recovery, the coroner will have to consider for the purposes of the assessment not only the residual physical damage but also the psychic one, since FGM has an important psycho-traumatic efficiency.