Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a disruptive effect on the entire healthcare landscape and therefore also on the hospital system, causing a reconsideration of the way services are offered which in the future will significantly affect the healthcare offer. The first wave hit a part of our region, and Brescia in particular, with unexpected brutality. Starting from the third week of February, after the identification of the first Coronavirus outbreaks (in the province of Lodi), the wave of the epidemic reached Brescia, with access to hospital emergency rooms which, from 23 February 2020 onwards, recorded a progressive impressive intensification. In our hospital (600 beds, Fondazione Poliambulanza – Istituto Ospedaliero, Brescia) in just under two months more than 2,200 patients were received and treated, 1450 of whom were hospitalized. A total of 186 patients were hospitalized in intensive care unit (during the most critical moment 430 Covid patients were hospitalized and up to 78 beds were set up and made available, compared to 21 in the ordinary times).

The hospital was completely transformed, with a revision of almost all operating paradigms: the birth point kept active and only 3 (out of 13) operating rooms, for emergency interventions and oncological emergencies; all elective admissions and all outpatient activities were blocked, strengthened the staff of the intensity (all the strengths and skills of resuscitators, anesthetists and operating room nurses have been destined for Covid-19 patients); specific training courses were organized for the doctors of different disciplines converted to Covid patient care (to support back-up in the departments and emergency room), 9 departments were converted and equipped for this function; over a hundred professionals were recruited from outside. The hospital has gone from a daily consumption in the ordinary situation of about 600 liters to 12,000 liters at the peak of the crisis (this involved the acquisition of additional tanks, the construction of new distribution and supply systems). The function of bed manager has been established: three operators always active controlling the beds’ occupation (of which, at the moment of maximum occupancy, 360 with ventilatory assistance at various levels of intensity) according to patients clinical and nursing care needs1. In summary, in a few days, forced by the overwhelming pandemic pressure, the hospital had to transform from a multi-specialty hospital to a Covid hospital and little time to work out a more appropriate process of care was left2.

The second wave

The second wave, which arrived in November 2020, again subverted the characteristics of the hospital, but on this occasion, thanks to the experience gained in the first wave, it was addressed by a more prepared and ready system with a specific organized response. Strengthened by the awareness that the organization, rather than the clinic (lacking now as then a specific effective treatment), would have produced the most favorable outcomes for patients, a modulated reception modality was immediately activated for the different types of patients: close monitoring of the most serious, intensive care in patients with more primary needs, interdisciplinarity and relationship with the community care for patients with greater home care needs to be satisfied once the hospital procedure is finished.

Even before Covid, our hospital, like many of the advanced hospital organizations, had started to shape the clinical paths accordingly to a multidisciplinary and transversal vision of care and applying models able to efficiently and effectively support processes for different cure needs (i.e. Progressive Patient Care & Patient Centered Care – PCC)3. The second wave of the pandemic has accelerated the ongoing change. This transformation, according to the creation of homogeneous paths by type of patients of different clinical severity and with different care complexity (model for intensity of care), was the intuitive organizational choice. This model was realized creating and assigning to different macro-areas of care, with specific and appropriate skills, patients with different disease severities and at different times regarding their disease trajectory.

Actions-Filter area (selection processes)

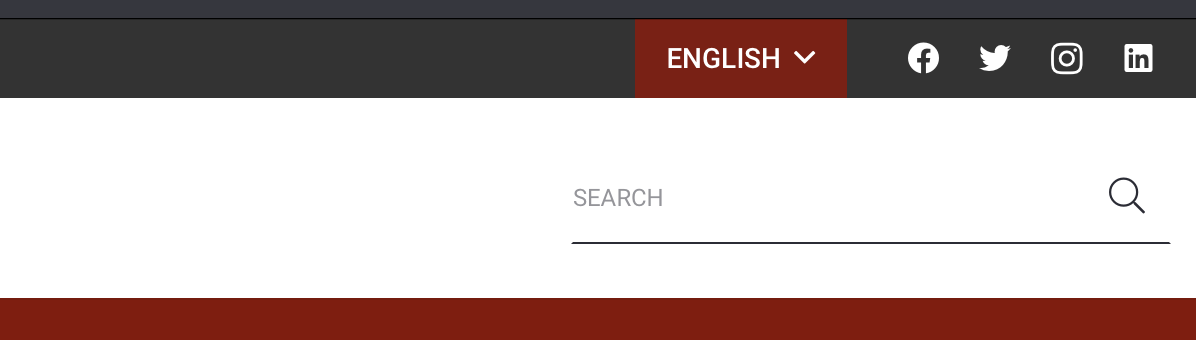

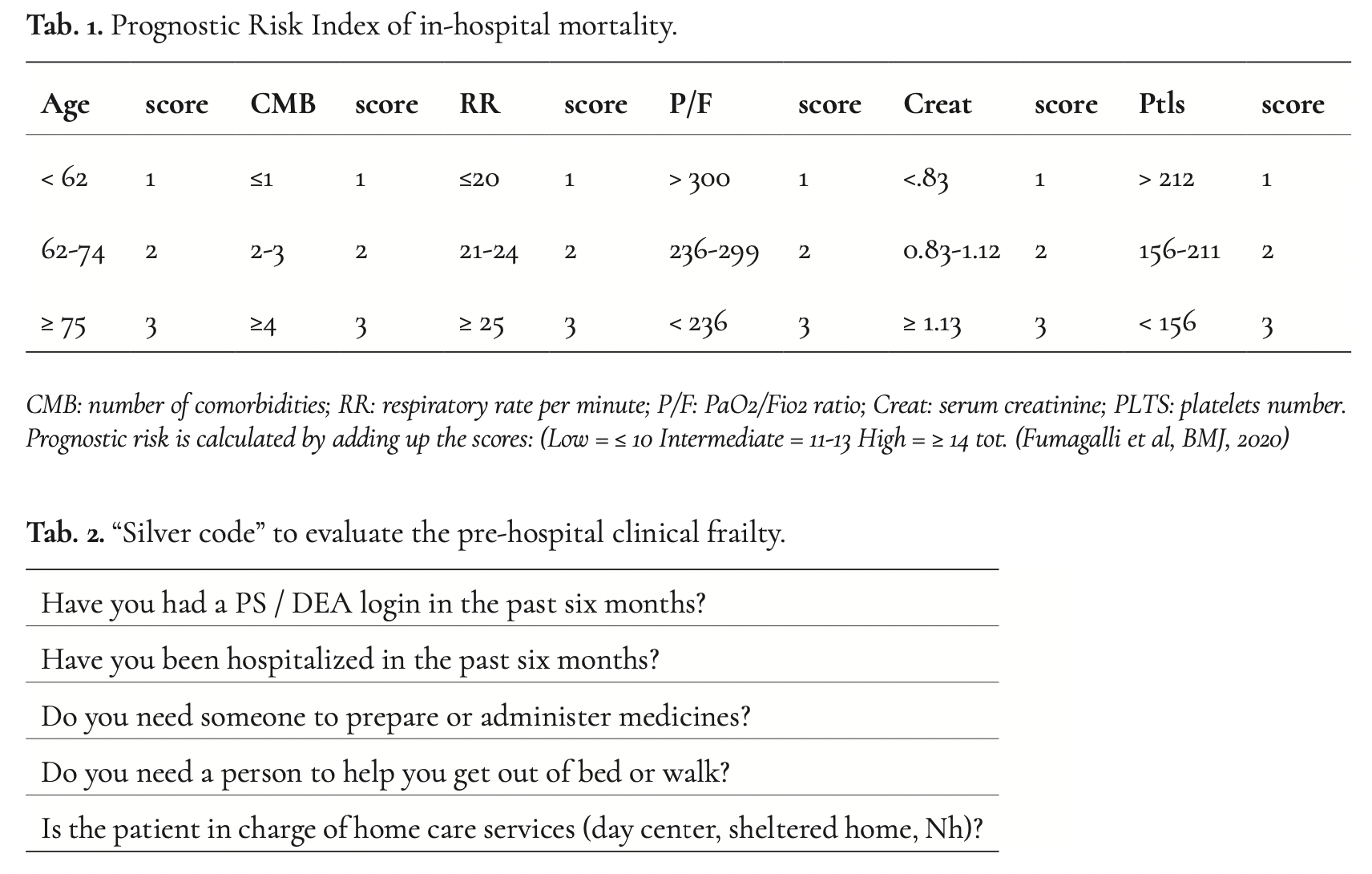

The first action taken was the creation of a high turnover area (“filter area”) reserved for patients from the ER with a definite indication for hospitalization and waiting for a swab report. In the filter area patients were stratified according to their clinical severity due to the Sars-Cov2 infection (by the Prognostic Risk Index of in-hospital mortality; Table 1), to their pre-existing medical status (i.e. comorbidity, disability), and to non-biomedical areas that could have influenced both the prognosis (aggravating factors) and discharge for each patient (The Silver Code, Table 2)4. The integration of the clinical characteristics with the comorbidities, functional status, and extra clinical ones (i.e. non biomedical factors) allowed the definition of:

- the patient’s health status (weight of the severity of the index pathology with respect to comorbidities or vice versa);

- the goal of care (lifesaving or maximization of palliative care and end-of-life comfort);

- the level of intensity of the treatments to be activated: intensive, global-comprehensive, palliative and comfort therapy, and basic.

The definition of patients’ characteristics and the treatment’s objectives allow the bed manager to manage the first allocation of the patients in a flexible way in the macro-areas designated (“ward triage”).

The macro-areas of hospitalization

The macro-areas of hospitalization

Specifically, 4 sectors (macro-areas) have been identified:

- a high-intensity sector called 2P Tower (it receives patients who require any type of therapy, potential candidates for transfer to ICU: in this sector, patients on non-invasive ventilation, patients with high-flow O2 delivery and Venturi Mask (VM) are admitted; this sector also receives patients who require palliative therapy, both for the management of NIV and in the terminality phase);

- a medium-intensity sector called 4P Tower (it accommodates patients with severe pneumonia or ARDS with no maximum need for O2 supply with MV);

- two low-intensity sectors respectively named 3P east and 4P tower (welcoming stable patients, with O2 delivery in CN, or clinically cured patients waiting to be transferred to specific post-acute settings (post-Covid settings) due to their inability to return home for environmental problems or for the worsening of the functional state following the Sars CoV-2 infection or the hospitalization).

Surgical patients with incidental Sars-CoV-2 infection were admitted to both the high and medium-intensity sector. The structure of the wards was naturally flexible, adapting to changes in both the state of health of patients and the epidemiology of demand (and the skills of the available assistance staff).

The assistance staff

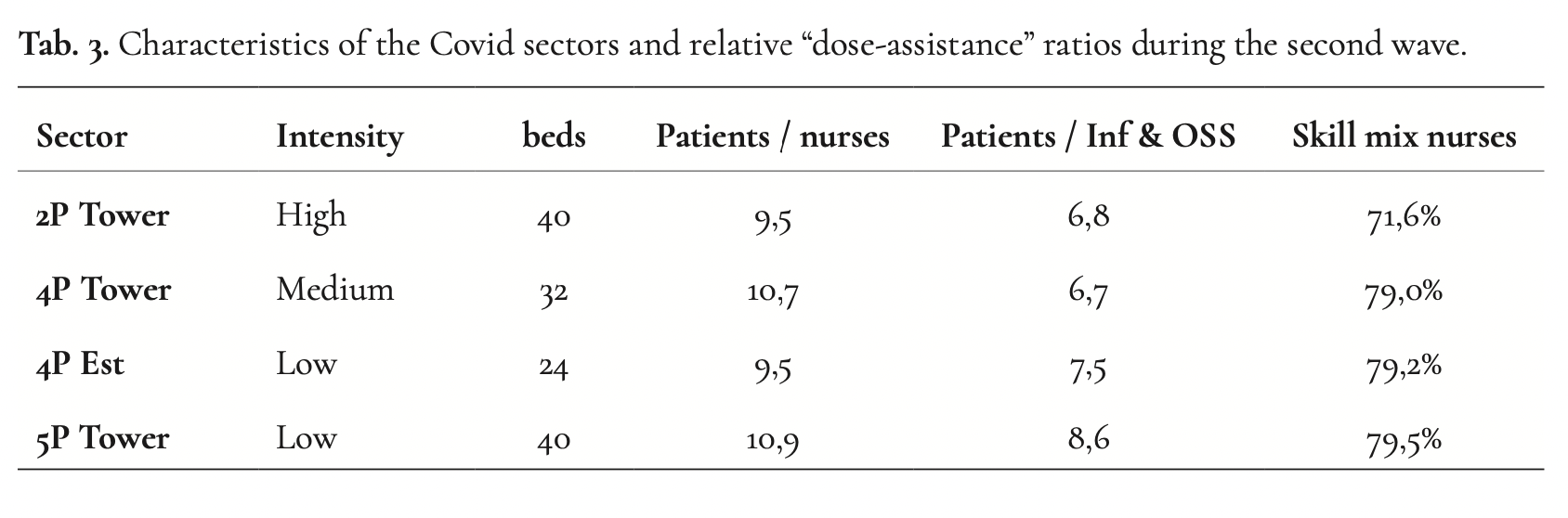

The adopted model required the placement of staff in the various settings by virtue of the skills possessed. As far as doctors are concerned, senior doctors with clinical skills and experience gained in the field of intensity were identified, were dedicated to lead the high and medium-intensity sectors, and junior doctors (capable, due to physical and mental energy, of maintaining the will and ability to continue working even in the most stressful and difficult conditions due to the mix of clinical and non-clinical aspects) were dedicated to lead the low-intensity sectors with high discharge rates. The doctors of the other specialties performed a support function. A conversion of Nurses and Social Health Operators of the surgical departments in Covid nurses was required; the presence of the staff was organized on the basis of their competence in the intensity of care and “measuring” their presence according to different “nurse-to-patient ratio” (Department of Health, UK, 2013). Skills and staff numbers were thus the organizational drivers, which combined with the clinical complexity of the patients made it possible to organize the intensity of care (Table 3).

After covid: lesson learned

Organization legacy built during the pandemic after the last covid patient was discharged:

- The function of bed manager has been definitively established; one operator is now active 24 hours a day (with control of the beds’ occupation), he responds to the requests of the emergency room concerning the placement of the patients according to their medical or surgical and nursing care needs.

- Multidimensional evaluation for all patients, detecting clinical severity, biomedical and functional burden, and non-biomedical needs (all of them able to influence prognosis and discharge feasibility) is adopted and performed in ER; now it is the tool used by the bed manager to allocate patients in the different wards.

- In surgical department the model for intensity of care (homogeneous paths by type of patients of different clinical severity and with different care complexity), was realized.

- Nurse to patient standard were revised and different “care dose” is now the rule adopted in all departments.

Conclusions

Conclusions

The Covid-19 crisis has imposed at the hospital level a reflection on the paths to be taken not only to redeem the many deaths, but to produce concrete and structural acts of recognition and protection for the entire population who will require hospital care5. To avoid being drained into the cynicism that the pandemic crisis will bring, hospitals can make pragmatic choices that favor the quality of care rather than the repetition of what is already known. Some suggestions learned:

- Flexibility. What happened for the emergency should have a follow-up in the ordinary. Ability to quickly change function to beds according to the required needs. This happened for emergency reasons. The design of new hospitals should consider this aspect, partly already achieved with the new hospitals designed according to the “intensity of care”. We should think of medical areas no longer separated by walls (and not only structural), but large areas where patients can access regardless of their acute clinical picture (special situations such as acute STEMI heart attack, stroke, for which to prepare areas flexible equipped).

- Co-management. During the pandemic infectious disease specialists, pulmonologists, internists and specialists from other disciplines each intervened on the individual patient according to his skills, going beyond what until yesterday was a single simple consultation. Co-management need to be an ordinary practice.

- Technology. During the pandemic we all realized how necessary it was to have efficient, easily maneuverable, not obsolete machinery. Not only ventilators but also ultrasound (vascular, cardiological, thoracic, abdominal) has facilitated diagnostics and consequently treatment. In large medical areas, at least 20-30% of “High Care” beds must be present, ie beds equipped with technology for monitoring vital parameters with relative observation and control unit.

- The competence. Specific skills will be needed but also general skills in all hospital wards. There will be an increasing need for doctors who are able to have an overall view of the problems of each individual patient, to distinguish their priorities, to coordinate their entire assistance and care during hospitalization.

- The structural organization. Even before the pandemic, the problem of the lack of adequate facilities for patients discharged from an acute care hospital but not yet in conditions capable of being managed at home was relevant. It is necessary to invest in “intermediate care” by creating ad hoc structures or by converting abandoned structures or those destined for other uses to this function.

- The relationship with the territory. The hospital must become an open structure as much as possible. The relationship with local doctors and, where present, with the local nurse must become a mandatory and possible path also with IT means.

The achievement of these goals will be possible if the rigid constraints overcome by the imperative necessity (and enthusiasm) of the first wave, but evident and limiting in the second, are overcome with regulatory, as well as intellectual flexibility, which allows operationally adapting the hospital’s responses to needs of the patient. Finally, organized systems require “discrete” information (objective assessment), which, while not representing indisputable references, allows more appropriate responses to the individual patient, and a more equitable distribution of available resources. However, it will be important to avoid the danger that the thought underlying the organization (the technology and technicality) can become dominant, overwhelming the ideal inspiration of the hospital which, instead, must take advantage of the organization and technology, but refuse to be dominated by them.