Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (UN-SDGs), are 17 goals with 169 targets that all UN Member States have agreed upon to work towards achieving by the year 20301. These have represented and represent a consensus on how we would like to change the world in order to ensure human beings a better, more equitable, sustainable and environmentally friendly future. However, progress toward the achievement of most SDGs was already lagging behind in 2019 and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is expected to slow down and, in some cases, reverse difficulty achieved improvements2,3. Why it is so hard to progress toward something so widely accepted?

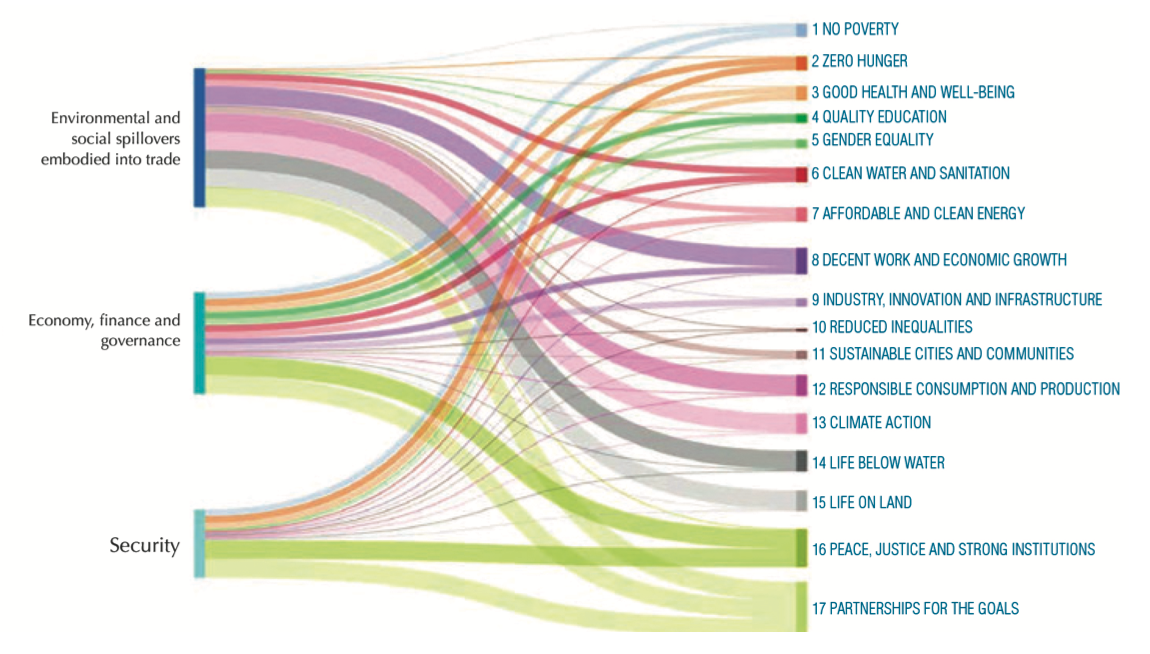

This has at least in part to do with the fact that these goals interconnect with numerous elements of the complex adaptive systems that we call “society”. For example, local conflicts, international financial and economic flows, migrations, pollutions and the economic and social impact of trades have direct and indirect spill-over effects on each of the SDG’s (Figure 1) and these, in turn, have a significant influence on each of these dimensions. This means, that achieving those goals inevitably impacts on lives and livelihoods, on conflicting priorities and interests consequently making their achievement less immediate. For this reason, documenting progress should not be taken for granted and recognized as a global achievement.

Fig. 1. Link between the three categories of spill-overs and the 17 SDGs. Source: Europe Sustainable Development Report 20204.

The emergence of a new virus (Sars-CoV-2) in 2019 and the consequent Covid-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on those same societies and represents a moment of dramatic break and regression in the general statement represented by the different issues posed by the SDG’s.

Firstly, the virus Sars-CoV-2 was hypothesized to be generated by a zoonotic jump (spill-over) from wildlife to humans, and the emergence of zoonotic disease is thought to be favored by human activities such as encroachment into wildlife habitats as a consequence of expanding urbanization, cropland area and intensive animal farming5.

Secondly, the pandemic emergency, which has almost reached two years of permanence, has highlighted the fragility of the health and social care systems of many countries, also the so-called “economically developed” ones. It has also sadly documented how difficult it is to ensure, in these circumstances, the acquired levels of welfare and the respect for the fundamental rights of human beings, so well represented by the SDG’s. Inequalities within and between countries have worsened and vulnerable and socially marginalized people have been able to access to a much lesser extent than the general population effective treatments or vaccination6.

As has been pointed out by the “Sustainable Development Report 2021”7: “[…] The pandemic has impacted all three dimensions of sustainable development: economic, social, and environmental. […] There can be no sustainable development and economic recovery while the pandemic is raging”.

This paper analyses the pandemic event from multiple angles specifically focusing on three mutually interconnected systems: healthcare, economies and society to try and identify elements that could shape possible post-pandemic evolution trends in policy and implementation models.

Pandemic complexity

As stated by Strumberg at al., the Covid-19 pandemic has the characteristics of “a ‘wicked problem’: we have not seen it arrive, we suffer its effects, and it challenges our main stream of reasoning”8. The uncertainties that have characterized this crisis and the global spread of this new pathogen have not only highlighted the underlying fragility of our health systems, but also the intrinsic and often underlying dynamics that characterize the pillars upon which these systems are based. In addition, it highlighted how changes in part of the system, for example in health systems, affect the entire society through interconnections that are not always evident.

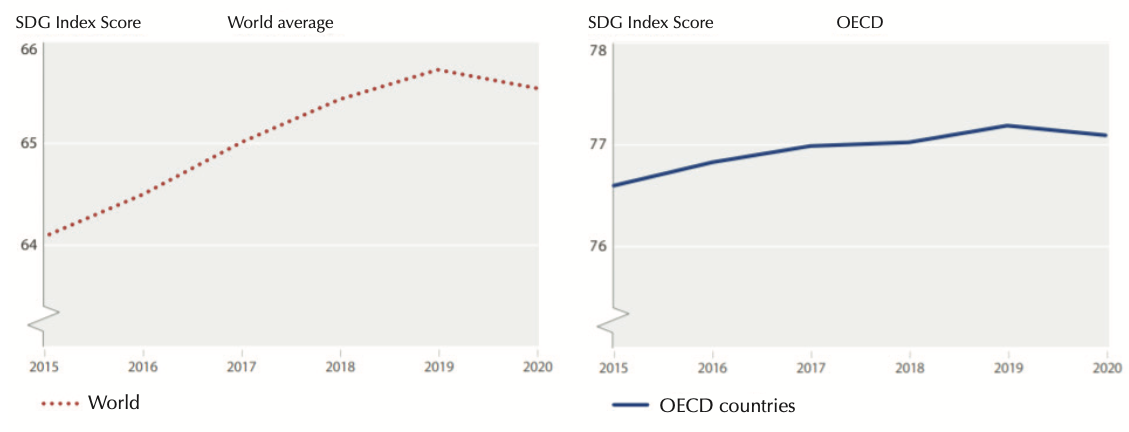

During this pandemic, for the first time since the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, the average global index of scores for the SDG’s has declined7. Dramatic consequences on a global level have been documented in terms of morbidity and mortality9, both as direct and indirect effects of the Sars-CoV-2 infection with profound consequences on economic progress, trust in governments, and social cohesion10. The degree of poverty of large sectors of the population has increased as a result11, deepening the gap between the richest and the poorest both within individual countries and between countries12.

A direct impact of the Covid-19 pandemic has also been recognized in the growth of global unemployment13, of violence against vulnerable groups14 and in the exposure and exacerbation of existing human and civil rights violations15,16. All these impacts have been disproportionally higher in more fragile contexts and population groups as is immediately visible if the worsening trend of the SDG index is calculated globally and only among OECD countries, where it is still present but less evident (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Annual trend of the SDG index (World and OECD countries). Source: 2021 Sustainable Development Report7

Healthcare Systems

Healthcare systems were severely affected by the pandemic with the surfacing of weakness in the management of this emergency, especially regarding the primary and community care sector. However, more resilient healthcare systems were quickly able to adapt to the new situation with a strong acceleration in the introduction of new organizational models and an extensive use of digital technologies. The interaction between patients and healthcare professionals and between professionals have moved, when possible, online, bringing the healthcare sector closer to other sectors more mature in the use of digital resources (e.g. banking transactions, travel and hotel reservations, purchases).

This has also opened up the possibility of task shifting and changes in existing organizational models that led for example to the enrolment of pharmacies in vaccination campaigns17, the transfer of cancer therapies from hospitals to home care18, the strengthen- ing of telemedicine and remote monitoring19,20, the consolidation of community nurses21, the spread of intermediate care22, and to growing investments in community homes and community hospitals, which in turn could initiate profound changes in our health systems and, consequently, in our society.

Under this dramatic pressure, these changes and innovations have allowed our healthcare systems to react to the various pandemic waves. While the next challenge will be to accurately assess their positive and negative effects in ordinary conditions, it should be recognized that the ability to access timely an adequate volume of vaccines, i.e. to access the main public health response to the pandemic23, has been inequitable across countries. Despite the COVAX initiative, promoted by numerous international public and private partners including the World Health Organization24, to date only 5.7% of populations in low-income countries have received at least one dose of the Sars-CoV-2 virus vac- cine25.

Economies

The pandemic has led to a dramatic fall in global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the International Monetary Fund estimates that if Covid-19 were to have a prolonged impact into the medium term, it could reduce global GDP by a cumulative $5.3 trillion over the next five years26. However, the pandemic impacted differently across industrial sectors with IT companies, online commerce and logistics generally benefiting as opposed to other sectors (e.g. tourism, recreation, accommodation, food services) that were hit hard and will require longer time to recover27. Economic impact has also differed among people, with young people, women, unskilled workers and undeclared workers among mostly penalized categories, and between countries with an earlier recovery in China, for example, compared with Europe28,29.

Different strategies in the application and enforcement of public health measures impacted the economy, social life and well-being of people differently. Therefore, a second noteworthy element of analysis rotates around the differences in the non-pharmacological interventions put in place by countries to contrast the spread of infections and their level of implementation. This includes the timing, type, duration, and intensity of restrictions imposed on populations within countries and the dynamics of restrictions and controls regulating mobility between countries. A clear example is represented by Italy that transitioned from a national lockdown in the first acute epidemic phase to a tired sub-national closure approach. Although both approaches have been shown to be highly effective in reducing viral transmission and, consequently, the impact of Covid-19 on health services30,31 the second approach was clearly associated with a smaller negative impact on the GDP32.

Additional negative economic consequences at a global level were caused by the more or less drastic closure of borders that has continued throughout the extended duration of this emergency and are being enacted again at the time of writing with the emergence of the omicron virus variant33. Among the hardest hit sectors, in this case, were those with a strong segmentation of production in different countries (Global Value Chain). Additionally, particularly during the first epidemic wave, these restrictions strongly impacted on the mobility of researchers with a reduction in the capital of ideas generated. This was subsequently compensated by alternative methods of virtual interaction34.

A recurring question that is being posed is what consequences this pandemic will have in the long term and how the supply and demand will change in different countries and among different population groups. Economic recovery, which began in the second half of 2021, appeared surprising in its speed and more sustained than expected, particularly if compared with the 2008 economic crash29.

This momentum, if not broken by pandemic resurgences, particularly if associated with radical changes in the model of development and coupled with policies aimed at the future generations (such as the Next Generation EU plan35) could have very positive repercussions on collective well-being and on the creation of a more just and equitable post-pandemic society.

Societal inequities

As of 31 October 2021, UNE- SCO data from 210 countries showed that the median cumulative duration of partial or total school closures during the pandemic has been of 33 weeks (range 0-77 weeks)36. Even when alternative distance learning solutions were provided, it is still difficult to quantify the negative consequences of school closures. Considering existing global inequities in access to education, internet and digital literacy, the immediate impact on learning achievements as well as the longer-term risk of exacerbating discrimination and inequality on a socioeconomic and geographical basis should be considered. Further, school closures have been an obstacle for the development and the well-being of children and adolescents and have been associated with negative health impacts, including, but not limited to, mental health37.

Gender inequities were also particularly evident during the Covid-19 pandemic. The female workforce was the most exposed to negative consequences for several reasons. Firstly, because women are prevalent in work sectors at higher risk of exposure and burn-out including health care professions and professions caring for elderly and disabled people. Specifically, among healthcare workers, women were found to experience more frequent and intense symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance and burnout38. Secondly, because women were increasingly victims of violence and aggression in general and within homes14 as economic and social stress coupled with restricted movement. Thirdly, because women’s employment loss increased almost immediately during the pandemic. This was in part due to their relevant presence in occupational sectors that were more exposed to the crisis such as tourism, hospitality, education and childcare. How- ever, it was also linked with an increased voluntary dropout from employment39 in a context in which women had to absorb an increased workload of unpaid activities such as childcare during school closures, family management, housework and home caring for elderly and/or disabled family members losing access to health and social services40. This has led to a 5% employment fall in 2020 among women, compared with 3.9% among men13. The loss of work among the female population has significant consequences for the well-being of the family that are likely to be on a long-term basis, given the greater difficulties women face in re-entering the work environment40. The disproportion of women in single-parent families has further aggravated many of the aspects described above. Lastly, under those circumstances, the reduced or lack of access to health care services, the disruption of maternal health and family planning services and in the supply of modern contraceptives has particularly affected women, with a consequent increase in unwanted pregnancies, abortions, and maternal mortality41,42.

A third element of social disparity43 during the pandemic was triggered by the change in the employment sector with a widespread use of remote work, facilitated by the extensive use of IT technologies. This has exacerbated the gap between work-from-home jobs (often more highly skilled work categories) and those that require physical presence (often low-skilled jobs or jobs that require direct contact with clients) that were more difficult to maintain. Within this dynamic context, an increase in atypical jobs was observed which generated a reduction in revenues for Health Services in countries with financing systems based on social insurance and formal work contribution. Workers depending on whether they could work from home or not, lost income during lockdowns and changed their mobility patterns during more permissive epidemic phases. This means that the use of public and private transports and of urban and public spaces also changed leading to disparities also in the risk of exposure to Sars-CoV-2.

Fragments of Hope

Although not compensating the negative effects of the pandemic, in these complex and worrying circumstances, some signals can be interpreted positively.

Unlike what happened during the 2008 economic crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic has activated more sustained solidarity and participatory mechanisms. National governments have played an important role in many countries in protecting the social safety of those less equipped to bear the brunt of the crisis. They did so by adopting financial and social protective mechanisms. Furthermore, governments of many high-income countries have directly intervened to protect national financial markets and national strategic companies against speculative and aggressive interventions and have directly and massively sponsored pharmaceutical research on innovation development. The latter was particularly evident for the development of vaccines against Sars-CoV-2 and has led to true technological innovations44.

At the international level it is noteworthy to mention the work of the European Union which, overcoming deep divergences between Member States, decided to remove the budgetary constraints that severely limited individual country actions and policies, and adopted the following initiatives:

- Changed to the EU budget to address urgently the health and economic crisis.

- Redirected EU funds to help Member States with the greatest needs.

- Supported the most affect- ed economic sectors.

- Negotiated and purchased vaccines for all Member States.

- Established the European instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE)45.

- Established the EU recovery plan, Next Generation EU35.

These interventions, which mark a pro-social and solidarity “u-turn” of Member States compared with pre-pandemic prevailing narratives, strengthen the European Union and could pave the way for greater cohesion and important political changes at international as well as internal level.

Other positive elements can be traced in the accelerating momentum for life-changing innovative processes with a strong presence of information technology spanning from health monitoring wearable devices to tools for molecular drug design44. The attitude towards public health systems has also changed. New value is being given once again to community and primary care, to the consolidation of public health and prevention as cornerstones to contrast the pandemic and in general the deterioration of global health, and to the strengthening of the concept of proximity in the provision of community health and social care.

During this emergency, healthcare systems have experienced new ways of working and implemented solutions that may well last beyond the pandemic itself. Even considering the evident and over-whelming negative impacts of the pandemic on the volumes and composition of healthcare services, which in some cases led to a reduction of up to 80% in elective surgeries, this crisis also forced health managers to consider whether all the things that were done in the past were necessary, appropriate, and just. Due to the increase in resource constraints, it was paramount to use available re- sources to support those services and procedures that would generate the greatest net benefit for patients prioritizing those in greatest need46,47.

Some aspects, such as the environmental crisis, global warming, the depletion of natural resources and the loss of biodiversity will have to find an adequate and consistent response with a new development perspective that will also bring undoubted benefits to the health of future generations. Likewise, prevention and preparedness against global health threats that are expected to arise more frequently because of these determinants will need policies framed around the need to address complexity and interconnectedness as is the case of the suggested One Health framework by the Global Health and Covid-19 Task Force of the 2021 G20 Presidency48.

Concluding Remarks

An aphorism by W. Churchill states: “To improve means to change, to be perfect means to change often”. We believe that it is of fundamental importance to exploit the learning opportunities that the dramatic crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has offered.

Innovations that were projected to take place many years from now, faced an extraordinary acceleration. The spread in current practice of digital tools for remote monitoring and management of patients, the ability to organize effectively massive vaccination campaigns, the large public investment in medical research and innovation, which led to the development and approval of innovative vaccines and rapid diagnostic systems at an incredible speed, the immense production of knowledge and its open sharing, the growing importance of behavioral and public health interventions are just some examples of successes that can generate permanent changes in health- care systems and in health care service delivery.

The need to define the global strategies for health and sustainable development was well understood by the WHO with the “Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development”49, which produced a report were seven recommendations are identified, namely:

- Make the One Health concept operational at all levels.

- Take action at all levels of society to heal the divisions exacerbated by the pandemic.

- Support innovation to achieve better One Health.

- Invest in strong, resilient and inclusive national health systems.

- Create an enabling environment to promote investment in health.

- Improve health governance globally.

- Improve health governance in the pan-European region.

If these seven recommendations will be implemented, we will have capitalized on this crisis and will be able to look to the future with greater optimism. The WHO, the European Union and the Italian Ministry of Health have all recognized the conceptual framework of reference in the “One Health” approach, that is clearly consistent with the SDG targets and also declinable in other frameworks such as those specific for Urban Health50.

We will need to restart after the pandemic and increase our efforts to achieve the SDG’s, but it will necessary to do so also changing the way we live and produce, taking advantage of the innovations that have been made available at an increasing pace. When, at last, the post-pandemic phase will arrive, however, we will not be starting from scratch.

This said it is undoubtedly that some well-known challenges and old foes still lie ahead. One Health needs to be understood, integrated and, most of all, operationalized in practice to deliver its full potential, SDG’s need to be re-prioritized in a new dimension of commitment and the positive changes that were introduced and implemented during the emergency capitalized upon to foster progress towards an equitably healthier world.